Deciphering cell’s recycling machinery earns Nobel

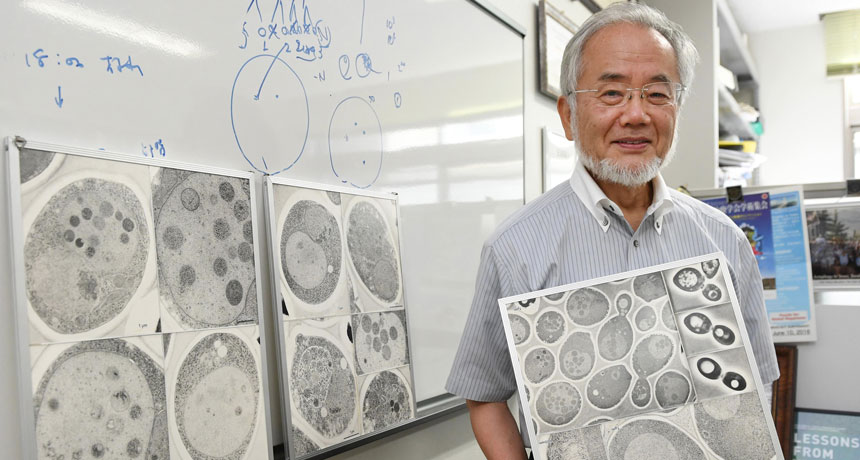

Figuring out the nuts and bolts of the cell’s recycling machinery has earned the 2016 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Cell biologist Yoshinori Ohsumi of the Tokyo Institute of Technology has received the prize for his work on autophagy, a method for breaking down and recycling large pieces of cellular junk, such as clusters of damaged proteins or worn-out organelles.

Keeping this recycling machinery in good working condition is crucial for cells’ health (SN: 3/26/11, p. 18). Not enough recycling can cause cellular trash to build up and lead to neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Too much recycling, on the other hand, has been linked to cancer.

“It’s so exciting that Ohsumi has received the Nobel Prize, which he no question deserved,” says biologist Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz of Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Va. “He set the framework for an entire new field in cell biology.”

Ohsumi‘s discoveries helped reveal the mechanism and significance of a fundamental physiological process, biologist Maria Masucci of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden said in a news briefing October 3. “There is growing hope that this knowledge will lead to the development of new strategies for the treatment of many human diseases.”

Scientists got their first glimpse of autophagy in the 1960s, not long after the discovery of the lysosome, a pouch within cells that acts as a garbage disposal, grinding fats and proteins and sugars into their basic building blocks. (That discovery won Belgian scientist Christian de Duve a share of the Nobel Prize in 1974.) Researchers had observed lysosomes stuffed with big chunks of cellular material — like the bulk waste of the cellular world — as well as another, mysterious pouch that carried the waste to the lysosome.

Somehow, the cell had devised a way to consume large parts of itself. De Duve dubbed the process autophagy, from the Greek words for “self” and “to eat.” But over the next 30 years, little more became known about the process.

“The machinery was unknown, and how the system was working was unknown, and whether or not it was involved in disease was also unknown,” said physiologist Juleen Zierath, also of the Karolinska Institute, in an interview after the prize’s announcement.

That all changed in the 1990s when Ohsumi decided to study autophagy in a single-celled organism called baker’s yeast, microbes known for making bread rise. The process was tricky to catch in action, partly because it happened so fast. So Ohsumi bred special strains of yeast that couldn’t break down proteins in their cellular garbage disposals (called vacuoles in yeast).

“He reasoned that if he could stop the degradation process, he could see an accumulation of the autophagy machinery in these cells,” Zierath said.

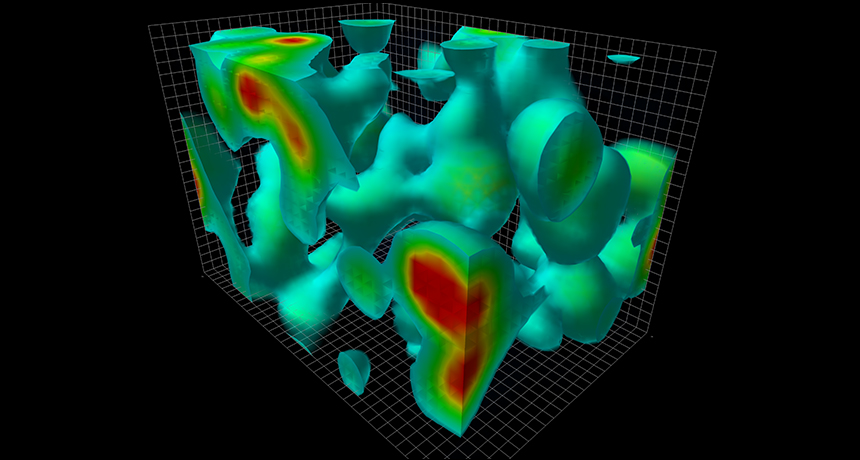

And that’s just what Ohsumi saw. When he starved the yeast cells, the “self-eating” machinery kicked into gear (presumably to scrounge up food for the cells). But because the garbage disposals were defective, the machinery piled up in the vacuoles, which swelled like balloons stuffed with sand. Ohsumi could see the bulging, packed bags clearly under a light microscope. He published the work in a 1992 paper in the Journal of Cell Biology.

Finding the autophagy machinery let Ohsumi study it in detail. A year later, he discovered as many as 15 genes needed for the machinery to work. In the following years, Ohsumi and other scientists examined the proteins encoded by these genes and began to figure out how the components of the “bulk waste” bag, or autophagosome, came together, and then fused with the lysosome.

The work revealed something new about the cell’s garbage centers, Zierath said. “Before Ohsumi came on the scene, people understood that the waste dump was in the cell,” she said. “But what he showed was that it wasn’t a waste dump. It was a recycling plant.”

Later, Ohsumi and his colleagues studied autophagy in mammalian cells and realized that the process played a key maintenance role in all kinds of cells, breaking down materials for reuse. Ohsumi “found a pathway that has its counterparts in all cells that have a nucleus,” says 2013 Nobel laureate Randy Schekman, a cell biologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Virtually every corner of the cell is touched by the autophagic process.”

Since Ohsumi’s discoveries, research on autophagy has exploded, says Lippincott-Schwartz. “It’s an amazing system that every year becomes more and more fascinating.”

Ohsumi, 71, remains an active researcher today. He received the call from the Nobel committee at his lab in Japan. The prize includes an award of 8 million Swedish kronor (equivalent to about $934,000). About his work, he said: “It was lucky. Yeast was a very good system, and autophagy was a very good topic.”

Still, he added in an interview with a Nobel representative, “we have so many questions. Even now we have more questions than when I started.”